In East Germany, official media showed that there were no depressed or unhappy people. However, the reality was that people were anything but happy in the GDR. Under state surveillance, creativity, curiosity, and free thinking were verboten. Punk music was the antithesis of everything the socialist state represented – a society restricted by conformist values.

Punk music first emerged in the UK in 1976 as a rejection of authority, characterised by non-conformity and expression of anti-establishment views. Bands such as the Sex Pistols, whose style can be described as aggressive, unrefined and sneering garnered increasing popularity in West Germany, which in turn was discovered by East Germans tuning into West German television and radio channels.

To understand why East Germans became attracted to the punk scene, we should examine the struggles of a disenfranchised youth. Since the beginning of the GDR state, music was subjected to a series of stringent regulations that discouraged individuality and emphasised uniformity. In a society in where freedom of expression was limited, punk represented an alternative space for youths experiencing a period of transition at the turn of the decade. They’d been back into a corner by the authorities with little choice but to rebel.

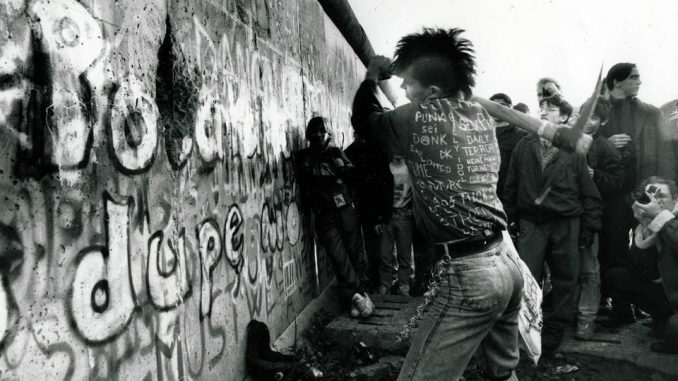

East German punks burst onto the scene around 1979, and in keeping with the ethos of their counterparts in the west, they sported spiked mohawks that were brightly coloured, leather jackets and metal studs or spikes. The government didn’t look too kindly upon the punk movement, especially its aesthetic factor, believing that these youths advertised the state in a negative light. Authorities also believed that punk was an attempt by the West German state to manipulate the masses. The volatile nature of punk music posed a serious threat to the strict regime of the East German state, and it became a necessity to crack down on the challenge to socialism.

“Every punk in East Germany risked everything: not only his present situation, but also his entire future as well” – Too Much Future

It was this first wave of punks that were successfully suppressed by the state; they were either sent to the army, forced into exile or sent to prison. Groups such as Namenlos and Planlos experienced first-hand the effects of the state intolerance of punk; they were continually sought out for persecution as means of rendering punk as an ineffectual method of protest. By using the punk scene as a platform to express contempt for a state that utilised repression in a declining economy, these outliers became systematic targets for authorities – simply because they dressed differently and dared to make themselves heard.

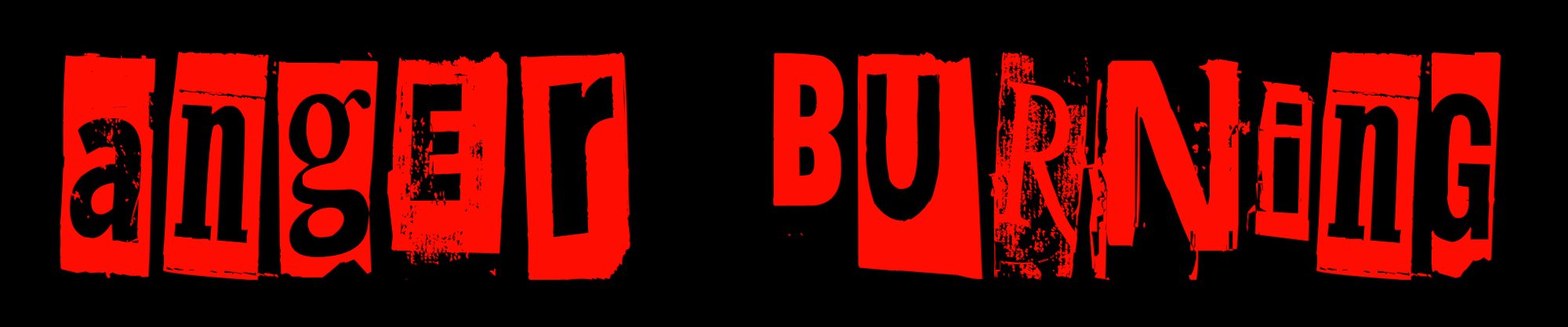

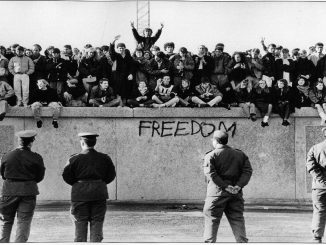

Temporarily succeeding in silencing the antagonistic punk movement, it wasn’t until 1984-5 that the second wave of punk appeared, but with a marked difference – just as its British predecessor had done, the once politically charged movement had split into a variety of sub-scenes. This period saw the emergence of Hardcore Punks, Anarcho-Punks, Wannabes, Art Punks, Skinheads and Neo-Nazi punks. The authorities were unable to make a distinction between these different groups, and it became more challenging for authorities to stamp out punk entirely. While punk in itself was symbolic of frustrations against the regime, the changing political climate towards the end of the decade meant there was no longer an urgent need to fight the system. When the wall was torn down in 1989, for the punk scene of East Germany, it was simple: the war on punk was finished – they’d won

Be the first to comment